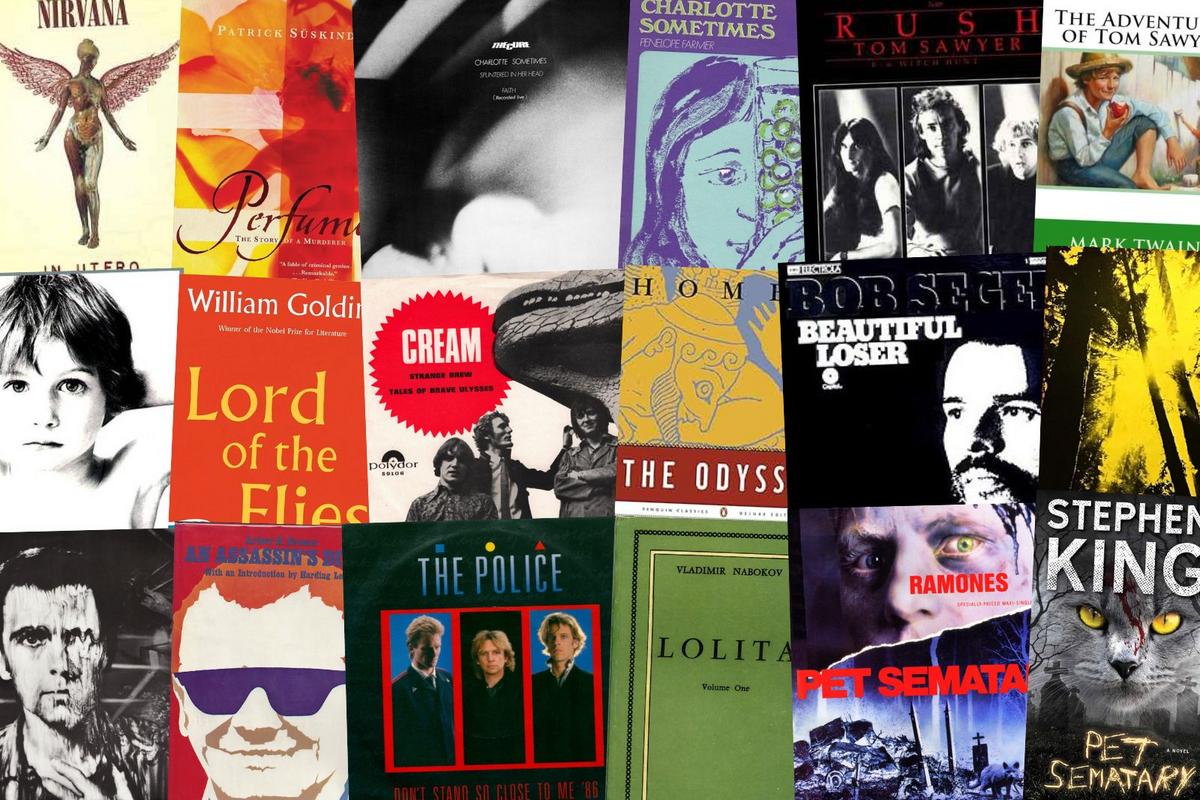

Jamming out to good music is a great time, but sometimes you just want to curl up with a good book.You can have the best of both worlds though —there are rock star book worms among us, and they’ve written quite a few songs based on novels, poems and more.Below, we’re taking a look at 60 Rock Songs Inspired by Books and Literature, for the most part limiting it to one entry per artist, in the interest of diversity and breadth.1. “The Battle of Evermore,” Led ZeppelinBook: Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien (1954)”The Battle of Evermore” is just one Led Zeppelin song inspired by J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. “Ramble On” and “Misty Mountain Hop” also include references to the 1954 fantasy novel.2. “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” MetallicaBook: For Whom the Bell Tolls, Ernest Hemingway (1940)For those who have not read Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, long story short: the Spanish Civil War was a brutal and bloody three-year event. Hence lyrics in the Metallica song like “Take a look to the sky just before you die / It’s the last time you will.”3. “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” Bruce SpringsteenBook: The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck (1939)Bruce Springsteen has created many compelling characters in his songs over the years, but one he cannot take credit for is Tom Joad, who came from John Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel set during the Great Depression, The Grapes of Wrath.4. “Sympathy for the Devil,” The Rolling StonesBook: The Master and Margarita, Mikhail Bulgakov (1966)When you picture Mick Jagger you probably don’t imagine him reading Soviet literature, but such was once the case. Jagger was reportedly given a copy of the Mikhail Bulgakov book The Master and Margarita not long after it was translated to English from Russian. Later came the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil,” and there is a central theme between the two works: evil does not always take the grotesque form one might assume it would.5. “White Rabbit,” Jefferson AirplaneBook: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll (1865)Grace Slick of Jefferson Airplane took away a pretty clear message from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. “All fairytales that are read to little girls feature a Prince Charming who comes and saves them. But Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland did not,” she told The Guardian in 2021. “Alice was on her own, and she was in a very strange place, but she kept on going and she followed her curiosity – that’s the White Rabbit. A lot of women could have taken a message from that story about how you can push your own agenda.”6. “Wuthering Heights,” Kate BushBook: Wuthering Heights, Emily Bronte (1847)There is an age-old debate: is it better to see the movie version of a story first or read the book? For Kate Bush, she happened to see the 1967 BBC adaptation of Wuthering Heights first, which then led her to read the 1847 novel and write the song “Wuthering Heights” in a single evening.7. “Scentless Apprentice,” NirvanaBook: Perfume, Patrick Suskind (1985)Nirvana’s “Scentless Apprentice” was inspired by a 1985 novel by the German writer Patrick Suskind called Perfume. In it, a Parisian orphan with an exceptional sense of smell grows up to become first a perfumer, then a murderer. A perfect premise for a rock song!8. “I Am the Walrus,” The BeatlesBook: The Walrus and the Carpenter, Lewis Carroll (1871)Lewis Carroll’s 1871 poem “The Walrus and the Carpenter” actually appears in his book Through the Looking-Glass, the sequel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. “To me, it was a beautiful poem,” Lennon told Playboy in 1980. “It never dawned on me that Lewis Carroll was commenting on the capitalist and social system. I never went into that bit about what he really meant, like people are doing with the Beatles’ work. Later, I went back and looked at it and realized that the walrus was the bad guy in the story and the carpenter was the good guy. I thought, oh, shit, I picked the wrong guy. I should have said, ‘I am the carpenter.’ But that wouldn’t have been the same, would it?”9. “1984,” David BowieBook: Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell (1949)Not only did David Bowie write a song titled “1984,” inspired by the George Orwell novel of the same name, at one point he had aspirations of writing an entire concept album about the book. Bowie was ultimately denied the proper rights to do this and turned the music he had written, including “1984,” into the 1974 album Diamond Dogs.10. “Pet Sematary,” RamonesBook: Pet Sematary, Stephen King (1983)Lots of Stephen King books have been made into movies, but what about songs? At one point, the legendary horror author and a self-proclaimed fan of Ramones met with them in Maine, where King lived then and where many of his novels are set. “We ate at Miller’s Restaurant, the only fancy restaurant in Bangor,” King recalled to Rolling Stone in 2014. “They showed up in their black leather jackets and torn jeans. Joey [Ramone] ordered steak tournedos. I don’t remember if we talked about Pet Sematary. I might have said something about a song. What I remember is that Marky [Ramone] was the only one who was articulate. The other ones really weren’t.” Ramones subsequently had their biggest U.S. hit with “Pet Sematary” in 1989.11. “2+2=5,” RadioheadBook: Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell (1949)You will begin to notice a pattern if you continue reading this list: Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four has inspired many, including Radiohead, who used one of the novel’s most famous lines, “2+2=5,” meaning the truth is whatever those in power say it is.”When I started writing these new songs, I was listening to a lot of political programs on BBC Radio 4,” Thom Yorke told Rolling Stone in 2003. “I found myself – during that mad caffeine rush in the morning, as I was in the kitchen giving my son his breakfast – writing down little nonsense phrases, those Orwellian euphemisms that our government and yours are so fond of. They became the background of the record. The emotional context of those words had been taken away. What I was doing was stealing it back.”12. “Colony,” Joy DivisionBook: In the Penal Colony, Franz Kafka (1919)Franz Kafka’s In the Penal Colony involves torture, execution, murder by machine and religious epiphanies, all of which evidently spoke to Ian Curtis of Joy Division, who drew inspiration from it for the song “Colony.” “[I]t’s got a literary reference to Kafka, which Ian was reading and I read a fair bit as well,” drummer Stephen Morris told GQ in 2020. “Whereas all the early songs were punky, thrashy things, we were trying to do stuff that was a bit unsettling. I really thought Ian’s lyrics on that one were absolutely fantastic.”13. “Charlotte Sometimes,” The CureBook: Charlotte Sometimes, Penelope Farmer (1969)”There have been a lot of literary influences through the years; ‘Charlotte Sometimes’ was a very straight lift,” Robert Smith said in a 2008 interview. The literary influence in question this time was also called Charlotte Sometimes, a 1969 children’s novel written by Penelope Farmer. In it, a young girl at boarding school suddenly finds herself time traveling backward 40 years.14. “Venus in Furs,” The Velvet UndergroundBook: Venus in Furs, Leopold von Sacher-Masoch (1870)Like the Velvet Underground song that it inspired, the 1870 book Venus in Furs by Leopold von Sacher-Masoch conjures up images of sadomasochism, bondage and general sexual power over another person.15. “Who Wrote Holden Caulfield?” Green DayBook: The Catcher in the Rye, J.D. Salinger (1951)Many of us read it in high school: J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Holden Caulfield serves as the outcast teenage narrator, and also as the star of Green Day’s “Who Wrote Holden Caulfield?,” “a boy who fogs his world and now he’s getting lazy.”16. “Brave New World,” Iron MaidenBook: Brave New World, Aldous Huxley (1932)Both the title track to Iron Maiden’s 2000 LP Brave New World and the accompanying album artwork draw inspiration from the 1932 novel of the same name. It’s a dystopian piece in which people have been scientifically modified and conditioned into a strict social hierarchy. Or, as Bruce Dickinson sings in the song, “you are planned and you are damned.”17. “Rocket Man,” Elton JohnBook: The Rocket Man, Ray Bradbury (1951)There have been lots of theories over the years as to what inspired Elton John’s “Rocket Man,” from the Space Race to drug usage. Lyricist Bernie Taupin, however, has said that the real inspiration was a short story by Rad Bradbury titled The Rocket Man, which appeared in a book of science fiction stories called The Illustrated Man.18. “Tom Sawyer,” RushBook: The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Mark Twain (1876)Like many school children, the members of Rush studied the work of Mark Twain in the classroom. Years later, Twain’s 1876 novel The Adventures of Tom Sawyer would inspire, of course, “Tom Sawyer” by Rush, which explored the book’s focus on heroism, rebellion and the intersection between them. “Neil [Peart] took that idea and massaged it, took out some of [cowriter] Pye [Dubois]’s lines and added his thing to it,” Alex Lifeson would later recall to Classic Rock.19. “Don’t Stand So Close to Me,” The PoliceBook: Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov (1955)”I wanted to write a song about sexuality in the classroom,” Sting explained of “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” in the 1981 book L’Historia Bandido. Well, where else to draw “inspiration” from — if one can call it that — than arguably the most famous book about an inappropriate relationship ever written, Lolita? The 1955 novel gets nodded to specifically in the song’s lyrics: “It’s no use, he sees her / He starts to shake and cough / Just like the old man in that book by Nabokov.”20. “Disturbance at the Heron House,” R.E.M.Book: Animal Farm, George Orwell (1945)Here’s a song about an Orwell book, but not Nineteen Eighty-Four. R.E.M.’s “Disturbance at the Heron House” instead has ties to Orwell’s 1945 novel Animal Farm, in which a group of, well, farm animals, overthrow their human masters to create their own society, a narrative with allusions to the 1917 Russian Revolution and subsequent Stalinist era.21. “All I Wanna Do,” Sheryl CrowBook: Fun, Wyn Cooper (1987)In 1987, poet and then-graduate student Wyn Cooper published a selection of his work in a book called The Country of Here Below. A piece titled Fun was included in the book, and within just weeks of its publication, Cooper got a call asking for permission to use the poem as the foundation of a song. He hastily agreed and the following year, with only a few small changes to the original words, Sheryl Crow had a hit with “All I Wanna Do.”22. “Among the Living,” AnthraxBook: The Stand (1978) and Apt Pupil (1982), Stephen KingAnthrax brings us back to Stephen King. “Among the Living” draws from two different King selections: 1978’s The Stand and 1982’s Apt Pupil. And frankly, you may not find a musician who is a bigger fan of the horror writer than Anthrax’s Scott Ian, who boasts a collection of dozens of rare copies of King books.”Even in the world of music, there’s no one bigger than him,” Ian explained to Metal Hammer in 2019. “I’ve never met Malcolm or Angus Young, but meeting Stephen King would be even bigger for me. Other than breathing and listening to music, reading Stephen King books is the one constant activity in my life. It pre-dates Anthrax.”23. “Behind the Wall of Sleep,” Black SabbathBook: Beyond the Wall of Sleep, H.P. Lovecraft (1919)Is it really any surprise that bands like Black Sabbath were drawn to the work of fantastical horror writer H.P. Lovecraft? “I was reading [H.P. Lovecraft’s short story] Beyond the Wall of Sleep, and actually fell asleep and dreamed all the lyrics and the main riff to [“Behind the Wall of Sleep”],” Geezer Butler recalled to Rolling Stone in 2020. “When I woke up, I wrote down the lyrics, played the riff on my bass so I’d remember it — we didn’t have any recording devices back then, so everything had to be memorized — and played it to the others at rehearsal.”24. “The Call of Ktulu,” MetallicaBook: The Call of Cthulhu, H.P. Lovecraft (1928)H.P. Lovecraft is perhaps most famous for being the man behind the Cthulhu Mythos, a sort of shared fictional universe involving various elements of Lovecraft’s writings. Metallica tweaked the spelling of it slightly for the “The Call of Ktulu,” which appeared on 1984’s Ride the Lightning.25. “Don Quixote,” Gordon LightfootBook: Don Quixote, Miguel de Cervantes (1605 and 1615)If you’ve never read 1605’s Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes, often considered one of the first modern novels, you could give Gordon Lightfoot’s “Don Quixote” a listen for a little taste of the story.25. “Golden Hair,” Syd BarrettBook: Golden Hair, James Joyce (1907)Before he started writing original songs for Pink Floyd albums, Syd Barrett spent some time setting poems penned by others to new music, including James Joyce’s 1907 piece Golden Hair.27. “Hedda Gabler,” John CaleBook: Hedda Gabler, Henrik Ibsen (1891)John Cale’s “Hedda Gabler” does not revolve around a book or poem, but instead the 1891 Henrik Ibsen play of the same name. It appeared on Cale’s 1977 EP Animal Justice, which also included, of all things, a cover of Chuck Berry’s “Memphis.”28. “Home at Last,” Steely DanBook: The Odyssey, Homer (1614)This writer tried on multiple occasions to read Homer’s The Odyssey and put it down each time. What she did not know until writing this piece was that she could have just listened to Steely Dan’s “Home at Last” and gotten more or less the same message.29. “Love and Death,” The WaterboysBook: Love and Death, William Butler Yeats (1885)Here’s another rock ‘n’ roll interpretation of the work of an esteemed poet, this time in the form of William Butler Yeats’ “Love and Death” as performed by the Waterboys.30. “Moon Over Bourbon Street,” StingBook: Interview With the Vampire, Anne Rice (1976)”[“Moon Over Bourbon Street”] was inspired by a book by Ann Rice, called Interview With the Vampire, a beautiful book about this vampire which is a vampire by accident,” Sting once explained. “He’s immortal and he has to kill people to live, but he’s been left with his conscience intact. He’s this wonderful, poignant soul who has to do evil, yet wants to stop. Once again, it’s the duality which interested me.”31. “The Mule,” Deep PurpleBook: Foundation Series, Isaac Asmimov (1942)Sci-fi fans may be familiar with this one. Deep Purple’s “The Mule” draws from Isaac Asminov’s Foundation series, first published in 1942. Decades of books followed, featuring the Mule character, an evil, manipulative force in the galaxy.32. “My Antonia,” Emmylou Harris and Dave MatthewsBook: My Antonia, Willa Cather (1918)We were also surprised to find a collaboration had taken place between Emmylou Harris and Dave Matthews, not exactly the world’s most obvious choice for duet partners. Nevertheless, they got together in 2000 for a song called “My Antonia” based on Willa Cather’s 1918 novel of the same name. The song details the relationship between the book’s two main characters, Antonia and Jim.”One day I got the idea to make it a conversation and the song just seemed to write itself,” Harris said back when the song was released on the album Red Dirt Girl. “Well, then I had to pick a ‘leading man.’ I had just done a show with Dave Matthews, and I loved the way we sounded together. And he did a simply beautiful job. He came up with a harmony on that chorus that really gave the song a second melody.”33. “Narnia,” Steve HackettBook: The Chronicles of Narnia, C.S. Lewis (1950)Between 2005 and 2010, three films were made based on The Chronicles of Narnia, originally a book series launched by C.S. Lewis in 1950. In between the book and film adaptions there was “Narnia” by Steve Hackett, the opening track to his 1978 album Please Don’t Touch! The song also features Steve Walsh of Kansas.34. “Richard Cory,” Simon and GarfunkelBook: Richard Cory, Edwin Arlington Robinson (1897)Paul Simon penned “Richard Cory,” a song based on Edwin Arlington Robinson’s 1897 poem of the same name, in 1965. The year after that, he and Art Garfunkel put it to tape for their second album, Sounds of Silence.35. “Telegraph Road,” Dire StraitsBook: Growth of the Soil, Knut Hamsun (1917)Two things inspired Mark Knopfler of Dire Straits when it came to the song “Telegraph Road” from 1982’s Love Over Gold. First and foremost, there was the real life road, also known as U.S. 24, which stretches for 70 miles. But also, Knopfler was then reading a book called Growth and Soil by Knut Hamsun, about a farming man who settles in rural Norway. The book won Hamsun the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1920.36. “Shadows and Tall Trees,” U2Book: Lord of the Flies, William Golding (1954)U2’s “Shadows and Tall Trees” takes its name from a chapter in William Golding’s famous Lord of the Flies. “It’s a story about how fear of one another — or fear of ‘the other’ in a metaphysical sense — can shape our imagination and twist our thinking,” Bono wrote in his memoir Surrender. “It’s a story about the end of innocence that still shapes my thinking and writing today.”37. “Such a Shame,” Talk TalkBook: The Dice Man, Luke Rhinehart (George Cockcroft) (1971)Talk Talk’s “Such a Shame” draws from a 1971 book called The Dice Man by Luke Rhinehart, the pen name for George Cockcroft. about a psychiatrist who makes decisions based on the roll of a die. “A good book, not a lifestyle I’d recommend,” lead singer Mark Hollis noted in a 1998 interview.38. “Tales of Brave Ulysses,” CreamBook: The Odyssey, Homer (1614)According to Eric Clapton, his roommate Martin Sharp wrote the lyrics to Cream’s “Tales of Brave Ulysses” as he was daydreaming about somewhere much warmer than England, and more specifically, where Homer’s The Odyssey takes place. “He was very fond of the Mediterranean islands,” Clapton told Record Mirror in 1967, “and he wrote the song last winter in his cold rooms, wishing he were out in the sun.”39. “A Single Spark,” David GilmourBook: Speak, Memory, Vladimir Nabokov (1951)David Gilmour’s “A Single Spark” is the most recently released song on this list, having appeared on his 2024 album Luck and Strange. The inspiration behind that song was a book by Vladimir Nabokov — not Lolita, but instead 1951’s Speak, Memory. “I can’t remember quite how he put it, but he said that life is a single spark between two eternities,” Gilmour explained to The Guardian in 2024.40. “A Trick of the Tail,” GenesisBook: The Inheritors, William Golding (1955)You could probably write whole books based off the stories in Genesis songs, but we digress. Genesis’ “A Trick of the Tail” drew inspiration from William Golding’s The Inheritors, a book about the gradual extinction of one of the last Neanderthal tribes and the newer humans that replace them. “The beast that can talk?” Phil Collins sings. “More like a freak or publicity stunt.”41. “Awaken,” YesBook: The Singer: A Classic Retelling of Cosmic Conflict, Calvin Miller (1975)Yes’ “Awaken” clocks in at over 15 minutes, an epic of a song, but it needs all that time to get the spiritual message across. Jon Anderson found some inspiration in the 1975 book The Singer: A Classic Retelling of Cosmic Conflict by Calvin Miller, in which the story of Jesus Christ is told through the form of a poem that compares Jesus to being like a singer whose voice cannot be silenced.42. “Beautiful Loser,” Bob SegerBook: Beautiful Losers, Leonard Cohen (1966)Leonard Cohen wore many hats during his career — both literally and figuratively. One of the figurative ones was author. In 1966, his second and final novel was released, titled Beautiful Losers. Years later, it would inspire the Bob Seger song. “That was really inspired by Leonard Cohen, whom I’ve always been a huge fan of,” Seger once told NPR. “And it struck me — boy, what a great title for a song, you know?”43. “Big Brother,” Stevie WonderBook: Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell (1949)We’re not done with Nineteen Eighty-Four songs. Here’s one from Stevie Wonder, an eerily prescient number from his 1972 album Talking Book. “Sometimes unfortunately violence is a way things get accomplished,” he explained to Rolling Stone in 1973. “‘Big Brother’ was something to make people aware of the fact that after all is said and done, that I don’t have to do nothing to you, meaning the people are not power players. We don’t have to do anything to them ’cause they’re gonna cause their own country to fall.”44. “Catcher in the Rye,” Guns N’ RosesBook: The Catcher in the Rye, J.D. Salinger (1951)Holden Caulfield, the main character in The Catcher in the Rye, is many things, not all of them good. There’s a fine line between misunderstood and mistreatment, outcast and asocial. Axl Rose wanted to comment on this dichotomy in Guns N’ Roses’ “Catcher in the Rye.”“For me, the song is inspired by what’s referred to sometimes as Holden Caulfield syndrome,” he said during a 2008 Q&A session (via uDiscover Music). “I feel there’s a possibility that how the writing is structured with the thinking of the main character could somehow reprogram, for lack of a better word, some who may be a bit more vulnerable, with a skewed way of thinking and tried to allow myself to go what may be there or somewhat close during the verses. I’d think for most those lines are enjoyed as just venting, blowing off steam, humor or some type of entertainment where it may be how others seriously live in their minds.”45. “A Child Called ‘It,'” BuckcherryBook: A Child Called It, Dave Pelzer (1995)This song is not for the faint of heart. Buckcherry’s “A Child Called ‘It'” is based on Dave Pelzer’s 1995 memoir, in which he describes suffering terrible child abuse at the hands of his own mother. Not long after releasing the song, Buckcherry participated in various events aimed to raise money for those also affected by child abuse. “If we can reach and save just one child or even their abuser from joining the terrible cycle of violence and abuse, then I will do whatever I can to support them,” singer Josh Todd said in a statement at the time. “As a father, I can’t bear to think of children being abused, and knowing that we will help point them in a direction where they can get help is very important to us.”46. “Eagle,” ABBABook: Jonathan Livingston Seagull, Richard Bach (1970)There is a bird to thank for the opening track to ABBA’s 1977 release ABBA: The Album. Well, a book about a bird to be more precise. Benny Andersson and Bjorn Ulvaeus drew from 1970’s Jonathan Livingston Seagull by Richard Bach, a novella about a seagull who, as he learns about his flying capabilities, learns more about himself in the process.47. “Do the Evolution,” Pearl JamBook: Ishmael, Daniel Quinn (1992)You’ve heard of doing the locomotion — how about doing the evolution as Pearl Jam once suggested? Eddie Vedder took inspiration from Daniel Quinn’s 1992 philosophical novel Ishmael, which informed other songs on 1998’s Yield, in addition to “Do the Evolution.””I’ve never recommended a book before, but I would actually, in an interview, recommend it to everyone,” Vedder said to Addicted to Noise in 1998. “My whole year has been kind of with these thoughts in mind. And on an evolutionary level, that man has been on this planet for three million years, so that you have this number line that goes like this [hands wide apart]. And that we’re about to celebrate the year 2000, which is this [holds hands less than one inch apart]. So here’s this number line; here’s what we know and celebrate.”48. “Family Snapshot,” Peter GabrielBook: An Assasin’s Diary, Arthur Bremer (1973)On May 15, 1972, a man named Arthur Bremer attempted to assassinate George Wallace, the then-governor of Alabama and a supporter of racial segregation. He spent 35 years in prison for the crime, but long before his release in 2007, Bremer wrote a book about his experience called An Assassin’s Diary. Several years after that, Peter Gabriel drew inspiration from the book for his song “Family Snapshot.””An Assassin’s Diary was a really nasty book, but you do get a sense of the person who is writing it,” Gabriel said to Sounds in 1980. “Bremer was obsessed with the idea of fame.”49. “I Hear You Paint Houses,” Robbie RobertsonBook: I Heard You Paint Houses, Charles Brandt (2004)Robbie Robertson scored many a film soundtrack during his career, drawing inspiration from a variety of places. When he was at work on the music for Martin Scorsese’s 2019 film The Irishman, he pulled from the 2004 book I Heard You Paint Houses. “‘I hear you paint houses’ is kind of gruesome in a way — it’s an expression for when you want to hire a killer,” Robertson explained to Rolling Stone in 2019. “‘Painting houses’ refers to the splattering of blood.”50. “Image of the Beast,” Procol HarumBook: Image of the Beast, Philip Jose Farmer (1968)Pete Brown, who wrote the lyrics to Procol Harum’s “Image of the Beast,” drew from the 1968 horror novel of the same name. “It’s like a kind of science fiction, pornographic, great Raymond Chandler kind of a book about L.A.,” he told Songfacts. “It’s very, very fantastical and very bizarre…I got some ideas out of that really. I’m a big science fiction fan, especially from ’50s and ’60s and ’70s stuff.”51. “Into the Nightlife,” Cyndi LauperBook: Into the Night Life, Henry Miller (1947)Art inspires art inspires art. Cyndi Lauper’s “Into the Nightlife” is an example of that, which stemmed, as she explained to Entertainment Weekly in 2008, “from the title of the Henry Miller book Into the Night Life, which inspired Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s A Coney Island of the Mind, which inspired me to describe the images of nightlife here in NYC.”52. “L.A. Woman,” The DoorsBook: City of Night, John Rechy (1963)Well before he joined a rock ‘n’ roll band, Jim Morrison was a voracious reader, absorbing the work of various poets, beat writers and philosophers like a sponge. Much of it influenced his work as a lyricist — “L.A. Woman” references John Rechy’s 1963 novel City of Night, which depicts some of the seedy yet alluring underbelly of Los Angeles, the Doors’ hometown.53. “Make Love Stay,” Dan FogelbergBook: Still Life With Woodpecker, Tom Robbins (1980)The basic plot of Tom Robbins’ 1980 novel Still Life With Woodpecker is this: an environmentalist princess falls in love with an outlaw bomber known as the Woodpecker. If that’s the type of story that interests you, you may also be interested in Dan Fogelberg’s song “Make Love Stay,” which was inspired by the book.54. “Mandinka,” Sinead O’ConnorBook: Roots, Alex Haley (1976)The Mandinka people are an African tribe that number in the vicinity of 11 million. In 1976, author Alex Haley penned a fictional book, Roots: The Saga of an American Family, describing the plight of one young 18th century Mandinka boy who is captured and sold into slavery. This book was the premise for Sinead O’Connor’s 1987 song, “Mandinka.”55. “Mind Games,” John LennonBook: Mind Games: The Guide to Inner Space, Robert Masters and Jean Houston (1972)In the early ’70s, John Lennon was more than content to do his own thing away from the spotlight and public stages. He occupied himself with other things, including reading. It was after reading 1972’s Mind Games: The Guide to Inner Space by Robert Masters and Jean Houston that Lennon wrote “Mind Games,” the title track to his 1973 album.56. “Mothers Talk,” Tears for FearsBook: When the Wind Blows, Raymond Briggs (1982)”The song stems from two ideas,” Roland Orzabal of Tears for Fears explained of “Mothers Talk” in the 1985 documentary Scenes From the Big Chair. “One is something that mothers say to their children about pulling faces. They say the child will stay like that when the wind changes. The other idea is inspired by the anti-nuclear cartoon book When the Wind Blows by Raymond Briggs.”57. “Pauline Hawkins,” Drive-By TruckersBook: The Free, Willy Vlautin (2014)When Patterson Hood got his hands on an advance copy of Willy Vlautin’s book The Free, everything moved quickly. He read the book — about a traumatized Iraq War veteran – and almost immediately wrote a song about it. “I’ve never done anything like that,” Hood told a live audience in early 2014. “I finished it on Saturday and wrote it on Sunday.”58. “Profession of Violence,” UFOBook: The Profession of Violence: The Rise and Fall of the Kray Twins, John Pearson (1972)The best kind of friends and bandmates are the ones who loan you books. This is how UFO ended up writing “Profession of Violence” based off the 1972 book The Profession of Violence: The Rise and Fall of the Kray Twins. “That was a book that I had, originally,” drummer Andy Parker recalled to Classic Rock in 2020. “I’m not sure if I leant it to Phil [Mogg] or he bought his own, but he’s always had this thing where he reads stories and gets idea for songs.”59. “Rhiannon,” Fleetwood MacBook: Triad: A Novel of the Supernatural, Mary Bartlet Leader (1973)You never know when inspiration will strike – Stevie Nicks, for example, just happened to stumble on the very thing that would spark one of her most popular songs. “It was just a stupid little paperback that I found somewhere at somebody’s house, lying on the couch,” Nicks explained to Classic Rock in 2023. “It was called Triad [by Mary Bartlet Leader] and it was all about this girl who becomes possessed by a spirit named Rhiannon. I read the book, but I was so taken with that name that I thought: ‘I’ve got to write something about this.’ So I sat down at the piano and started this song about a woman that was all involved with these birds and magic.”60. “Sons of 1984,” Todd RundgrenBook: Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell (1949)To close things out, here’s one last Nineteen Eighty-Four song, this time called “Sons of 1984” by Todd Rundgren. “The idea behind the song was things could go one way and things could go another way,” he told Songfacts. “And the whole idea behind Nineteen Eighty-Four was abrogation of your will to authority. So, the song essentially was about whether the coming generation would have the strength or the will to continue to resist that authority and maintain their own autonomy.”44 Rock Artists Who Wrote Film ScoresRock ‘n’ roll represented on the big screen.Gallery Credit: Allison Rapp